Nordic Atlas of Language Structures (NALS) Online, Vol. 1, 1

Copyright © M. Julien and P. Garbacz 2014

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License

Prepositions expressing source in Norwegian

Marit Julien & Piotr Garbacz

Lund University & University of Oslo

1. Introduction

The preposition that marks the source argument of the verb få ‘get’ in the two written varieties of Norwegian, Bokmål and Nynorsk, is av. The same preposition is also found in this function in many spoken varieties, as in (1), an example taken from the Nordic Dialect Corpus.

|

(1) |

eg |

fekk |

rasarbane |

av |

farmor |

og |

faffar |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

|

I |

got |

racing |

course |

from |

grandma |

and |

grandpa |

|

|

|

‘I got a racing course from grandma and grandpa.’ (gjesdal_01um) |

||||||||

Av, which historically is a continuation of the Old Scandinavian preposition af (Bjorvand & Lindeman 2007:64), also has a number of other uses in Norwegian, as seen e.g. in the entries for av in Beito et al. (1966) and Guttu et al. (1977). Some of these uses, all attested in the Nordic Dialect Corpus, are shown in (2)–(6). In (2), we see the ablative use of av, whereas it marks cause in (3), material in (4), the whole in a part-whole relation in (5), and the agent of a passive in (6).

|

(2) |

så |

sjiffta |

demm |

take |

demm |

ræiv |

av |

all |

stæin |

|

|

|

then |

changed |

they |

roof.DEF |

they |

tore |

off |

all |

stone(DEF) |

|

|

|

‘Then they pulled the leaves off the twigs.’ (enebakk_03gm) |

|||||||||

|

(3) |

eg |

bler |

dårli |

av |

McDonalds-mad |

|

|

|

I |

become |

sick |

from |

McDonald-food |

|

|

|

‘I get sick from McDonald’s food.’ (stavanger_01um) |

|||||

|

(4) |

matpyllseddn |

da |

va |

bærre |

av |

innmat |

|

|

|

food.sausages.DEF |

that |

was |

only |

from |

offal |

|

|

|

‘The sausages were made from offal only.’ (aurland_ma_02) |

||||||

|

(5) |

dæ |

var |

en |

del |

av |

livet |

|

|

|

it |

was |

a |

part |

of |

life.DEF |

|

|

|

‘It was a part of life.’ (stange_02uk) |

||||||

|

(6) |

di |

bi |

tadd |

med |

av |

fårelldra |

|

|

|

they |

become |

taken |

with |

by |

Parents |

|

|

|

‘They are taken (there) by their parents.’ (stamsund_02uk) |

||||||

When it comes to the expression of the source argument of få ‘get’, as in (1), there is however considerable variation in Norwegian, and there are a few other prepositions that can be used in the same function: tå, ut av, hos (Almenningen 2005: 619), hjå (Almenningen 2005: 506), and med (Almenningen 2008: 1215). In the Nordic Syntax Database and in the Nordic Dialect Corpus we find data that can be used to shed some light on this variation. For space reasons, Scandinavian varieties other than Norwegian will not be taken into consideration.

2. Results

2.1 Nordic Syntax

Database (NSD)

In the ScanDiaSyn survey, in which the data for the Nordic Syntax Database were collected, the prepositions other than av which were tested in phrases expressing the source argument of the verb få ‘get’ were hos, hjå and med (but not the preposition tå).

The basic function of the preposition hos, found in all varieties of Norwegian that have this preposition at all, is as a marker of location, taking a human or at least animate complement. An example is given in (7), where hos åss means ‘at our place’. Another relatively common use of hos is exemplified in (8), where hos barn means ‘in children’ and denotes the existence of a property in a group of individuals (cf. e.g. the entry for hos in Landrø and Wangensteen 1986). The construction exemplified in (8) has a wide distribution in the sense that it is not associated with any particular variety of Norwegian. It can however be noted that it belongs to a relatively formal register. Accordingly, there are no occurrences of it in the Nordic Dialect Corpus (NDC), which contains only informal speech.

|

(7) |

ho |

bor |

i |

føssjtetasjn |

hos |

åss. |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

she |

lives |

in |

first.floor.DEF |

HOS |

us |

|

|

|

‘She lives on the ground floor at our place.’ (hammerfest_04gk) |

||||||

|

(8) |

Søvnproblemer |

hos |

barn |

er |

svært |

vanlige. |

|

|

|

sleep.problems |

HOS |

children |

are |

very |

common |

|

|

|

‘Sleep problems in children are very common.’ (Bokmål Norwegian) |

||||||

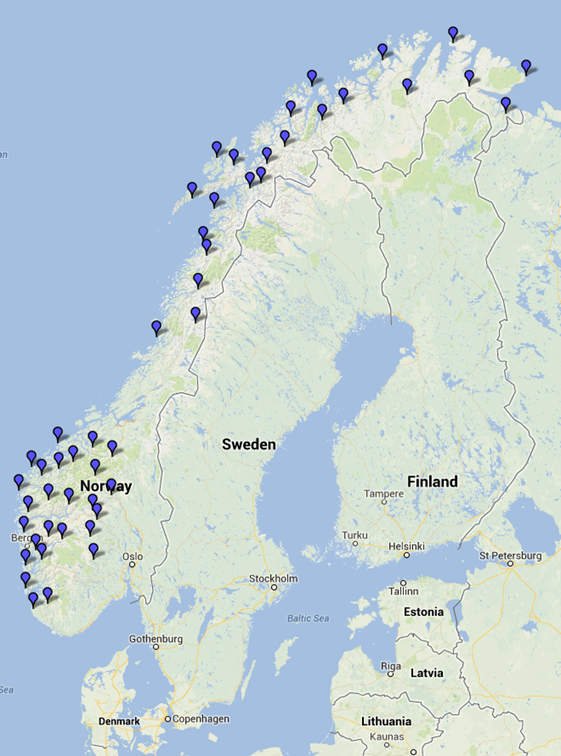

Historically, the preposition hos has developed from the noun hus ‘house’ (Bjorvand & Lindeman 2007: 506). In Old Norse, the corresponding locative preposition was hjá, from the noun hjá ‘married couple’ (Bjorvand & Lindeman 2007:515). In Danish and Swedish, hos had replaced hjá already in the Old Scandinavian period, and it has later replaced hjá in most varieties of Norwegian. Hjá is still found in Faroese and Icelandic. In addition, in its present-day forms like jå or sjå, it is used in dialects in the central and Western parts of Southern Norway, and in the form hjå it is also an alternative to hos in Nynorsk. In Bokmål, hos is used, and in many spoken varieties, we find hos or some variant of hos, like håss, åss, oss. Map 1 shows the distribution of (forms of) hos and hjå in present-day spoken Norwegian.

Map 1: The distribution of hos and hjå in Norway in the Nordic Dialect Corpus (NDC).

(Black = hos (with variants), white= hjå (with variants)).

In addition to expressing location, the Old Norse preposition hjá was also found after verbs like fá ‘get’, where a phrase headed by hjá expressed the source argument (cf. Heggstad, Hødnebø and Simensen 1990: 187). This usage has been retained in certain parts of Norway, and accordingly, the test sentence shown in (9) was presented to informants in those areas that have retained (a form of) hjå.

|

(9) |

e |

fekk |

hanskane |

hjå |

Per |

Ivar |

(#996, Eidfjord) |

|

|

I |

got |

gloves.DEF |

from |

Per |

Ivar |

|

|

|

‘I got the gloves from Per Ivar.’ |

||||||

In many locations in the counties of Møre og Romsdal and North and South Trøndelag, the preposition med was used, as in (10), which shows the test sentence used in Volda, in Møre og Romsdal county.

|

(10) |

E |

fikk |

hainskainn |

med |

n |

Per |

Ivar |

(#996, Volda) |

|

|

I |

got |

gloves.DEF |

from |

him |

Per |

Ivar |

|

|

|

‘I got the gloves from Per Ivar.’ |

|||||||

The core meaning of the preposition med is ‘with’. Throughout Scandinavian, it is used with an instrumental or comitative meaning. In Norwegian, and in particular in the dialects, it is however a very versatile preposition, as described e.g. in Almenningen et al. (2008: 1215).

Further, in some dialects of Norwegian, the source marking function that hjå had in Old Norse has spread to the newer preposition hos. Hence, outside the areas where hjå or med were tested, the preposition used in the test sentence corresponding to (9) and (10) was hos, as in (11).

|

(11) |

e |

fikk |

hanskan |

hos |

Per |

Ivar |

(#996, Ål) |

|

|

I |

got |

gloves.DEF |

from |

Per |

Ivar |

|

|

|

‘I got the gloves from Per Ivar.’ |

||||||

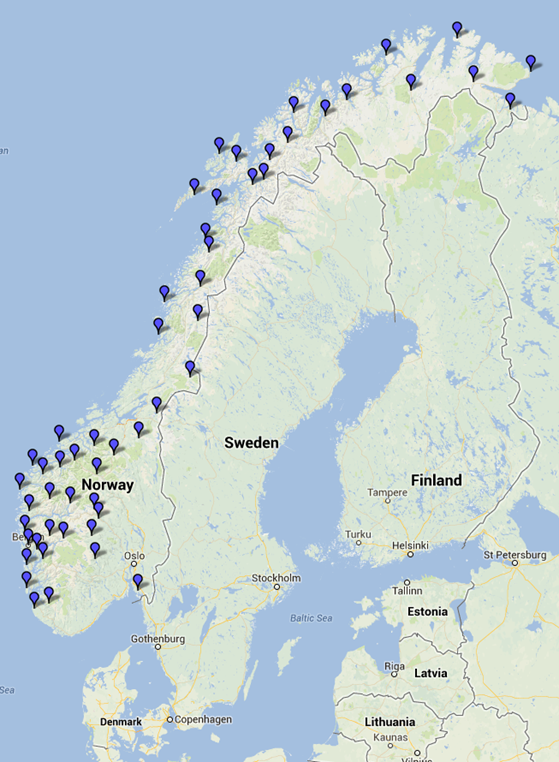

The locations where one of the three prepositions hos, hjå or med marking the source of få ‘get’ were generally accepted are shown in Map 2. We see here that the acceptance of these prepositions form two large clusters: one in the north and another in the west-central part of Southern Norway.

Map 2: Locations where the prepositions hos, hjå or med expressing source got a high score.

(#996: Jeg fikk hanskene hos Per Ivar. ‘I was given the gloves by Per Ivar’)

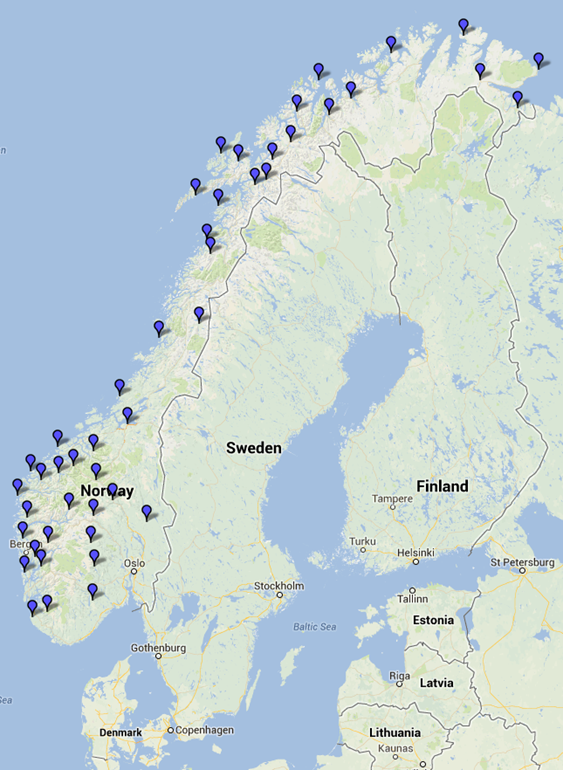

The overall distribution of judgments shown in Map 2 does not differ much between age groups. As maps 3 and 4 show, the survey results among informants aged 50+ (map 3) were very much the same as the results among informants aged between 15 and 35 (map 4).

Map 3: Locations where the prepositions hos, hjå or med expressing source got a high score

among older informants (50+ years)

(#996: Jeg fikk hanskene hos Per Ivar. ‘I

was given the gloves by Per Ivar’)

Map 4: Locations where the prepositions hos, hjå or med expressing source got a high score

among youger informants (15-30 years)

(#996: Jeg fikk hanskene hos Per Ivar. ‘I

was given the gloves by Per Ivar’)

If we look at the details of the database, we see that hos expressing the source of få ‘get’ was accepted by almost all informants in the three northernmost counties of Norway, i.e. Finnmark, Troms and Nordland, from Sømna in the south to Kjøllefjord in the north. In Nordland, it was rejected by the young informants from Herøy as well as by one young man from Mo i Rana, and in addition, there was variation among informants from Kautokeino and Lakselv, two locations in Finnmark. In Kautokeino, it was accepted by a young man but rejected by a young woman and an old man, while it got a medium score from an older woman. In Lakselv, it got a high score from the older informants but a medium score from the younger informants. The divergences from the general pattern found in Kautokeino and Lakselv might be connected to the fact that many speakers in these locations come from a Sámi-speaking background, or alternatively, in Lakselv, from a Finnish-speaking background. This might be the reason why they have not completely adopted the use of hos found in other speakers from the north of Norway. However, in other locations where there are many speakers with Sámi as their first language, such as Tana, hos marking source was nevertheless fully accepted. Hence, there are still unanswered questions in this area.

In the county of Møre og Romsdal, the test sentence in (10), with med, was largely accepted. This in accordance with the distribution suggested in Almenningen et al. (2008). In the counties of North and South Trøndelag, on the other hand, it was rejected by most speakers.

In the counties of Sogn og Fjordane and Hordaland, as well as in the mountain areas of Buskerud and Oppland and also in some places in Rogaland, the (basically) locative preposition hjå was largely accepted as a marker of source. In Ål, hos was tested and accepted by all informants. In Gausdal, close to Lillehammer, sjå, the local form of hjå, was however rejected by all informants.

In the counties of Hedmark, Akershus, Østfold, Vestfold, Aust-Agder, Vest-Agder and Telemark, forms of sjå marking source were tested in the locations Valle and Tinn, and rejected in Valle but accepted in Tinn. Elsewhere in this area, hos was tested and rejected, with a few exceptions: hos was accepted by one older woman in Kristiansand, by the older informants in Fredrikstad, and by younger informants in Nissedal and Rena. It is possible, though, that some of these results are false positives, since (11) would be grammatical throughout the region with hos Per Ivar meaning ‘at Per Ivar’s place’.

In the Trøndelag region, consisting of the counties North and South Trøndelag, the picture that emerges is quite complex. The results from this region will be discussed in the next subsection, where the survey data are combined with data from the Nordic Dialect corpus.

2.2 Nordic Dialect Corpus (NDC)

Turning now to

the Nordic Dialect Corpus, we will first look at occurrences of få ‘get’ with the

basically locative prepositions hos

or hjå

(including variants) marking the source. Examples of this are found in a number

of places in the NDC. First, forms of hos

with this function are attested in Northern Norway, in the counties of Finnmark (Kirkenes, Kjøllefjord), Troms (Botnhamn, Kirkesdalen, Kvæfjord, Kvænangen, Lavangen, Tromsø, Tromsøysund), and Nordland (Bodø, Hattfjelldal, Herøy, Myre, Stamsund). There are also

occurrences of forms of hjå

in the West Norwegian counties of Sogn og Fjordane (Luster) and Hordaland (Lindås,

Voss), as well as in Lesja and Lom in the county of

Oppland and Flå in the county of Buskerud. All these

locations are shown in Map 5.

Map 5: The prepositions hos/hjå expressing source, as attested in

the Nordic Dialect Corpus. (Black = places of attestation).

Some of the authentic examples from the corpus are given in (12)–(16) below.

|

(12) |

å |

så |

fikk |

hann |

besje |

åss |

sekretæærn |

sin |

att… |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

and |

so |

got |

he |

message |

at |

secretary.DEF |

REFL.POSS |

that |

|

|

|

‘And then he got a message from his secretary that…’ (kirkenes_03gm) |

|||||||||

|

(13) |

ka |

du |

fikk |

hoss |

ho |

# |

Berta? |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

what |

you |

got |

at |

she |

|

Berta |

|

|

|

‘What did you get from Berta?’ (myre_02uk) |

|||||||

|

(14) |

så |

dæ |

fikk |

ho |

hoss |

me |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

so |

that |

got |

she |

at |

me |

|

|

|

‘So she got that from me.’ (stamsund_03gm) |

||||||

|

(15) |

e |

fekk |

fæmm |

krone |

jå |

tanntå |

mi |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

I |

got |

five |

crowns |

at |

aunt.DEF |

my |

|

|

|

‘I got five crowns from my aunt.’ (lindaas_03gm) |

|||||||

|

(16) |

kann |

e |

få |

æin |

fasit |

jå |

deg? |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

can |

I |

get |

a |

key |

at |

you |

|

|

|

‘Can I get a key from you?’ (voss_04gk) |

|||||||

As it turns out, all the examples with hjå from the southern part of Norway in the corpus are produced by older informants. This is not necessarily significant, however, since there are not many expressed source arguments of få ‘get’ in the corpus at all. The absence of examples produced by younger speakers in the south could therefore be a coincidence. In the survey, hjå marking source was accepted by younger and older informants alike in Lindås, Luster, Lom, and Voss, while it was rejected by all informants from Flå. There are no data from Lesja in the survey. Taken together, the data appear to suggest that hjå as a marker of source is falling out of use in Flå, which is the location closest to Oslo in map 5. In the other locations in the south where it is attested at all, it is probably still retained.

In the north, by contrast, hos expressing source is attested in younger informants as well as in older ones. It was also accepted by almost all informants, with the exceptions mentioned in the previous subsection. This suggests that hos is or is becoming the preferred marker of the source argument of få ‘get’ throughout the north of Norway.

In the county of Møre og Romsdal, where the preposition med expressing source got high scores in the survey, we also find similar examples in the corpus. Moreover, these are from younger speakers as well as from older speakers. The example in (17) is produced by an older man, while the example in (18) is produced by a younger man.

|

(17) |

ho |

får |

pottet |

me |

me |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

she |

gets |

potato |

from |

me |

|

|

|

‘She gets potatoes from me.’ (surnadal_18) |

|||||

|

(18) |

tja |

fekk |

ittje |

ho |

Marte |

et |

tilbud |

me |

na |

då |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

well |

got |

not |

she |

Marte |

an |

offer |

from |

him |

then |

|

|

|

‘Well Marte got an offer from him, didn’t she?’ (heroeyMR_01um) |

||||||||||

Hence, corpus data as well as survey data suggest that med as a marker of source is not disappearing in this area. In fact, it extends into the neighboring county to the south, Sogn og Fjordane, where an example with med is attested from Stryn.

A twist that should be mentioned here is that the informant from Surnadal who produced (17), with me(d), was presented with an example with hos in the survey. He rejected this example, and so did the other informants from the same location. Hence, it appears that the preposition chosen by the investigators here failed to reveal the actual usage in the local dialect.

From the Trøndelag region there are only three instances in the corpus of få ‘get’ with an expressed source argument. In all these cases, which are shown in (19)–(21), the preposition is tå.

|

(19) |

å |

så |

hi |

dæmm |

fått

|

besje |

tå |

mora |

te |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

and |

then |

have |

they |

got |

order |

from |

mother.DEF |

to |

|

|

|

‘and they got an order from their mother to….’ (inderoey_03gm) |

|||||||||

|

(20) |

æ |

fekk |

melling |

tå |

n |

Hans |

|

|

|

I |

got |

message |

from |

he |

Hans |

|

|

|

‘I got a message from Hans.’ (skaugdalen_36) |

||||||

|

(21) |

han |

ha |

fått |

friarbrev |

på |

donngvis |

tå |

ei |

utnlannsk |

ei |

|

|

|

he |

has |

got |

proposal.letters |

on |

heap.wise |

from |

a |

foreign |

one |

|

|

|

‘He has got heaps of letters of proposal from some woman abroad.’ (skaugdalen_36) |

||||||||||

The preposition tå has developed from ut-av ‘out-of’ (see e.g. Rietz 1867:770-771, Aasen 1873), and in many dialects of Norwegian, it has replaced av — in some varieties in the form ta. Where tå or ta is used instead of av, these prepositions are in general found in the same contexts as av in the standard varieties.

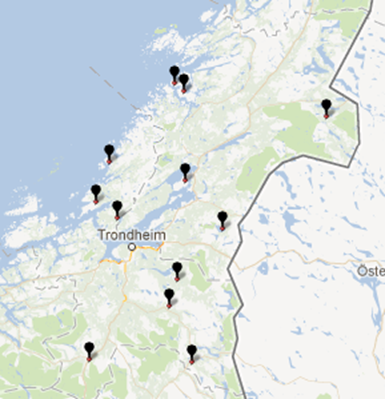

However, the preposition used in Inderøy in the relevant test sentence in the survey was med, whereas hos was used in Skaugdalen. These options were rejected by all the informants in these locations. And since tå marking source arguments was not tested in the survey, we do not know how widespread the use of tå is. What we do know, however, is that the preposition tå is used in other contexts in many places in the Trøndelag region. We see this in map 6, which shows occurrences of tå regardless of function. The only location represented in the corpus that does not have any instances of tå is Trondheim, the main city of the region. This in accordance with the general tendency that tå is associated with traditional rural dialects rather than with urban dialects.

Map 6: The preposition tå in the Trøndelag region.

In addition to Skaugdalen, hos was tested as a source marker in Bjugn and Stokkøya, which both are situated on the coast to the north-west of Trondheim. The judgments were however negative, with the exception of younger informants in Stokkøya, who found it fully acceptable. In light of this, it is striking that in the corpus material from Stokkøya, there are no occurrences of the preposition hos at all. Instead, there is an example of the preposition te being used with the meaning ‘at someone’s place’, where the standard varieties of Norwegian would use hos or hjå. The example, which is uttered by a young woman, is shown in (22).

|

(22) |

æ |

e |

te |

mor |

mi |

i |

hælgen |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

I |

am |

at |

mother |

my |

in |

weekends.DEF |

|

|

|

‘I spend the weekends at my mother’s.’ (stokkoeya_31) |

|||||||

The basic meaning of te is illative, i.e. it corresponds to English to (and to til in the standard varieties of Norwegian). In (23), we see the same speaker using te in an illative function:

|

(23) |

vi |

kjæm |

sikkert |

fram |

i |

titia |

te |

hotellet |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

we |

come |

likely |

forward |

in |

ten.time.DEF |

to |

hotel.DEF |

|

|

|

‘We are likely to arrive to get to the hotel around ten.’ (stokkoeya_31) |

||||||||

Hence, it is not clear what the survey results from Stokkøya mean. It could be added, though, that the preposition hos is not much used in the Trøndelag region at all. In the corpus, only three of the informants from this region have occurrences of hos: an older woman from Trondheim, an older woman from Inderøy, and a younger woman from Oppdal. In all three cases, hos marks location at a human referent. In addition, sjå is found in Oppdal and sje in Lierne; both sjå and sje are variants of hjå. Apart from these cases, prepositions other than hos or hjå are used to express ‘at someone’s place’ in Trøndelag, and other prepositions are also used to express the source argument of få ‘get’.

In the latter function, med was tested in a number of places in Trøndelag. As already mentioned, it was rejected in Inderøy, and also in Namdalen and Røros. It was accepted by the older informants in Oppdal, Gauldalen and Lierne, while in Meråker and Selbu, it was accepted by some of the younger informants as well as by the older ones. Finally, in Trondheim it was rejected by the older informants but accepted by the younger ones. These results seem to suggest that med is falling out of use as a marker of source in most places in Trøndelag, with the exception of Trondheim, where it appears to be gaining acceptance. However, although younger informants from Trondheim reported in the survey that they accept med in this function, there are no examples of it in the corpus. Moreover, native speakers inform me that they would use te or av. Corpus data confirm that these prepositions are both used in Trondheim, although there are no examples where they express the source argument of få ‘get’. Which prepositions are actually used in this function in Trondheim will have to be investigated further.

A preposition that has not yet been mentioned is åt, from Old Norse át, which has a number of uses in Norwegian dialects (and in Nynorsk). Its basic meaning is ‘to, towards; for’ (see e.g. Hovdenak 1986), and it is also frequently used as a possessive marker. A search in the Nordic Dialect Corpus reveals that åt is found in all parts of Norway, with the exception of Sogn og Fjordane county. This does not mean that it is found everywhere outside this county, since it is clearly associated with traditional rural dialects. But interestingly, some speakers of Trøndelag dialects inform me that they would use tå as a marker of the source argument of få ‘get’. There are however no examples of this usage in the corpus, and since it was not tested in this function in the survey, the precise distribution of tå as a marker of source is not known.

What we can tell from the corpus is that åt is found in the same contexts as te, i.e. with locative or illative meaning, as shown in (24) and (25) (these examples should be compared to (22) and (23)). In addition, in some dialects åt replaces tå or av. In (26), we have an example where many other dialects would have tå or av.

|

(24) |

de |

va |

væll |

likæns |

åt |

dåkk |

å |

de? |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

it |

was |

PRT |

similar |

at |

you.PL |

too |

it |

|

|

|

‘I guess it was the same at your place?’ (roeros_03gm) |

||||||||

|

(25) |

hann |

sykkla |

jo |

åt |

staa |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

he |

biked |

you.know |

to |

town.DEF |

|

|

|

‘He biked to town, you know.’ (roeros_03gm) |

|||||

|

(26) |

hann |

bodde |

på |

n |

annre |

sidn |

åt |

sjøa |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

he |

lived |

on |

the |

other |

side.DEF |

of |

lake.DEF |

|

|

|

‘He lived on the other side of the lake.’ (roeros_04gk) |

||||||||

Note that (24), (25) and (27) are all from the same location. It is evident that in the Røros dialect, åt is a multifunctional preposition. Moreover, since its meaning overlaps with te, and also with av and tå, which all appear as markers of the source of ‘få’ in Norwegian, it is perhaps not very surprising that åt can also be found in this function.

While there is much variation in the Trøndelag region as to how the source argument of få ‘get’ is expressed, there is little variation in other areas. In the western part of Norway, to the south of the areas where we find med or hjå, only av is attested in the corpus. One of the occurrences was shown in (1), and another one is given in (27).

|

(27) |

eg |

fekk |

jo |

nye |

rullesji |

av |

onngane |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

I |

got |

you.know |

new |

roller.skis |

of |

children.DEF |

|

|

|

‘You know I got new roller skis from my children.’ (karmoey_03gm ) |

|||||||

In the south of Norway, and in the coastal areas around Oslo, we also find av, whereas inland from Oslo we find ta or tå. One example of each from the corpus are shown in (28) and (29).

|

(28) |

dømm |

fæ |

litt |

avlasstning |

tå |

en |

aan |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

they |

get |

a.little |

help |

of |

each |

other |

|

|

|

‘They get a little help from each other.’ (gausdal_08gk) |

|||||||

|

(29) |

så |

fækk |

je |

en |

ta |

onngkeln |

min |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

then |

got |

I |

one |

from |

uncle.DEF |

my |

|

|

|

‘Then I got one from my uncle.’ (alvdal_03gm) |

|||||||

3. Discussion

The review of relevant data from the Nordic Syntax Database and the Nordic Dialect Corpus given above shows that there is considerable variation in Norwegian with respect to prepositions marking the source argument of få ‘get’. It should further be noted that only phrases representing the source in transfer of possession are taken into account. To express a source of communication or the source in transfer of location, other prepositions are used, such as frå in (30) and (31).

|

(30) |

e |

fekk |

brev |

frå |

han |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

I |

got |

letter |

from |

him |

|

|

|

‘I got a letter from him.’ (alvdal_04gk) |

|||||

|

(31) |

jæi |

hadde |

fått |

di |

frå |

Jonnsrusaga |

(Norwegian) |

|

|

I |

had |

got |

them |

from |

Jonsrud.sawmill.DEF |

|

|

|

‘I had gotten them from the Jonsrud sawmill.’ (lommedalen_ma_02) |

||||||

A corpus search for få followed by frå (the form found in Nynorsk and in many dialects) or fra (the Bokmål form, also found in many spoken varieties) suggests that the usage seen in (30) and (31) is common in all parts of Norway.

Greater variation is seen in the preposition marking the source in transfer of possession, as already mentioned. Interestingly, the geographical distribution of the prepositions is quite clear. In the north, i.e. in the three northernmost counties Finnmark, Troms, and Nordland, we find hos, which primarily marks location at a human referent, here as well as in many other parts of Norway.

In the county of Møre og Romsdal, me(d) is the preposition most frequently used to mark the source of få ‘get’. Me(d) is an old Germanic preposition, found all over Scandinavia in a number of functions (see e.g. the entries for med in Almenningen et al. 2008 and Svenska akademiens ordbok 1893–). That it can also mark the source of få ‘get’ is noted in Almenningen et al. (2008), and strikingly, the authentic examples given there are all from Møre og Romsdal or from neighboring counties. In addition, Almenningen et al. (2008) observes that med can even be used in the meaning ‘at someone’s place’, i.e. as a locative marker with a human complement. Again, the examples are mainly from Møre og Romsdal county. Hence, it appears that in this county, med has partly the same functions as hos has in the north. As one can see from Map 1, neither hos nor the synonymous hjå is found in Møre og Romsdal, and it follows that some other preposition has taken over the functions that hos or hjå has elsewhere.

A question that now arises is why hos or med should mark both location and source. Syncretism of location and source is found also in other languages, although it is not very frequent (see Pantcheva 2010). In the case at hand, the fact that hos and med take a human complement when they mean ‘at someone’s place’ as well as when they mark the source of få ‘get’ could have paved the way for the syncretism. Recall that it had applied to hjá already in Old Norse, and it has later spread to hos in the north and to med in Møre og Romsdal. In addition, it is retained with hjå in the areas to the south of Møre og Romsdal and inland from there, in those locations where hjå is still in use.

In the Trøndelag region, which is located between Møre og Romsdal and Nordland, we find forms of hjå marking location in the southern periphery (Oppdal) and in the eastern periphery (Lierne). However, in these locations, and also in some other locations in Trøndelag, med was accepted as a marker of the source of få ‘get’, in particular by older informants. This indicates that med has been used in this function earlier, perhaps alongside hjå.

Elsewhere the Trøndelag region, the preposition that is attested as a marker of the source og få ‘get’ is tå, which has developed from and is synonymous with the standard form av – the basic meaning of both is ‘of, off, from’. In many varieties of Norwegian, not only in Trøndelag, but also in all locations to the south of the area where hjå is used, av or tå (including the variant ta) has replaced the locative preposition hjå as a marker of source.

However, although it is not attested in the corpus, I have been informed by speakers from Trøndelag that the preposition marking the source argument of få ‘get’ in many places and for many speakers is åt or te, which are found in all locations in Trøndelag that are represented in the corpus and in the database, with the exception of Trondheim, where te is found but not åt. In all other locations, there is variation between individual speakers, and even in individual speakers. This variation appears to reflect a situation where te is replacing the more archaic åt. A nice illustration of the variation is seen in (32), which is uttered by a young woman from Meråker:

|

(32) |

hjemme |

åt |

oss |

… |

når |

n |

e |

heim |

te |

mamma |

|

|

|

home |

ÅT |

us |

|

when |

one |

is |

home |

TE |

mother |

|

|

|

‘home at our place… when one is at my mother’s’ (meraaker_02uk) |

||||||||||

An interesting point here is that åt and te have illative meaning in other contexts. This means that in many places in the Trøndelag region there is syncretism of goal (illative) and source, instead of syncretism of location and source. As Pantcheva (2010) points out, syncretism of goal and source is another infrequent pattern in the world’s languages. Hence, the marking of the source argument of få ‘get’ in Norwegian in general and in Trøndelag in particular is very interesting from a typological point of view.

References

Aasen, Ivar. 1873. Norsk Ordbog : med dansk Forklaring, Mallings

Boghandel, Christiania.

Almenningen, Olaf et al. (eds.)

2008. Norsk ordbok : ordbok over det

norske folkemålet og det nynorske skriftmålet, vol. 7: L - mugetuft, Det

Norske Samlaget, Oslo.

Beito, Olav T. et al. 1966. Norsk ordbok : ordbok over det norske folkemålet og det nynorske

skriftmålet, vol. 1: A - doktrinær, Det Norske Samlaget, Oslo.

Bjorvand, Harald and Fredrik Otto Lindeman.

2007. Våre arveord. Novus, Oslo.

Guttu, Tor, Kåre Skadberg and Inge Wettergreen-Jensen. 1977. Riksmålsordboken, Kunnskapsforlaget, Oslo.

Heggstad, Leiv, Finn Hødnebø and Erik

Simensen. 1990. Norrøn ordbok, Det

Norske Samlaget, Oslo.

Hovdenak, Marit (ed.)

1986. Nynorskordboka, Det Norske

Samlaget, Oslo.

Landrø, Marit Ingebjørg and Boye Wangensteen (eds.) 1986. Bokmålsordboka,

Universitetsforlaget, Bergen.

Pantcheva, Marina. 2010. The

syntactic structure of locations, goals and sources. Linguistics 48:5, 1043–1081.

Rietz, Johan Ernst. 1867. Svenskt dialekt-lexikon : ordbok öfver svenska allmogespråket,

Lund.

Svenska akademien (ed.) (1893–). Ordbok över svenska språket. Akademibokhandeln Gleerup, Lund.

Web sites:

Nordic Atlas of Language

Structures (NALS) Journal: http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nals

Nordic Dialect Corpus:

http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nota/scandiasyn/index.html

Nordic

Syntax Database: http://www.tekstlab.uio.no/nota/scandiasyn/index.html